Mitochondrial Transplantation team and members of Mito2i: Erika Beroncal, Sonya Brijbassi, Ori Rotstein, Mikaela Gabriel, Ana Andreazza, Sowmya Viswanathan, Milica Radsic and Frank Gu (supplied image)

Funding Mitochondrial Transplantation for Regenerative Medicine

Ana Andreazza, PhD, professor of pharmacology and toxicology at the University of Toronto’s Temerty Faculty of Medicine, leads the Mitochondrial Innovation Initiative, Mito2i, a research hub at University and affiliated institutions and hospitals.

The new project, MitoRevolution: Mitochondrial Transplantation Transforming Regenerative Medicine — from research to patient care to global impact, is part of the university’s

Institutional Strategic Initiative portfolio, is supported by a $23.8-million grant from the Canadian federal government’s New Frontiers in Research Fund Transformation Stream and brings together an interdisciplinary team that is committed to transforming regenerative medicine through mitochondrial transplantation.

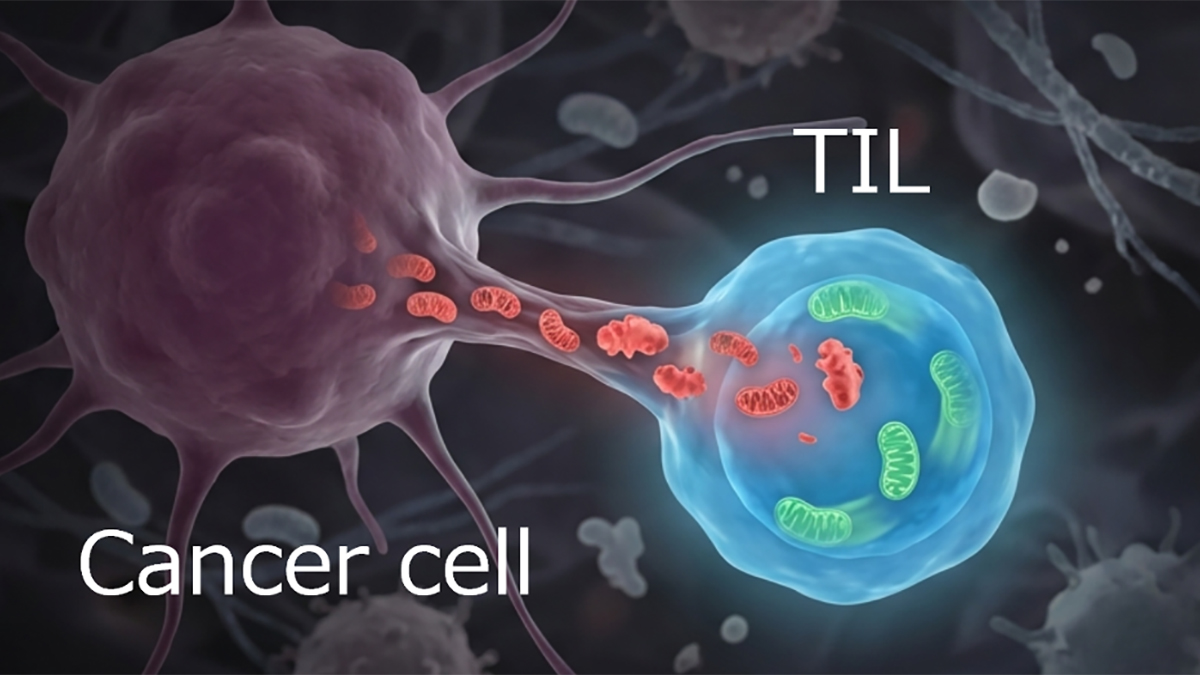

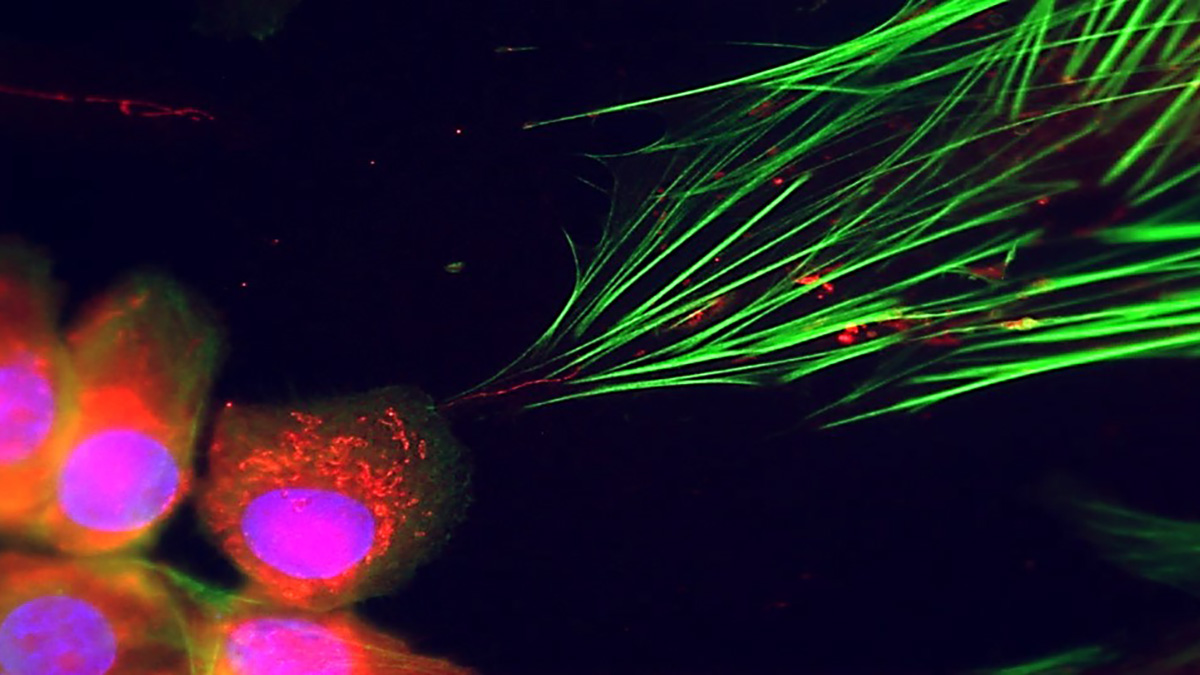

Mitochondrial transplantation is defined as the process of introducing new mitochondria into cells, tissues or organs, and mitochondrial transfer is the natural movement of mitochondria between cells or into bodily fluids.

These processes are both controversial, and mitochondrial transplantation as a therapy is viewed with a considerable skepticism. Nevertheless, there is a growing interest in research into transplantation for emergency, resuscitation and regenerative purposes. Some cases have yielded positive results. However, those results cannot be attributed to an increase in mitochondrial capacity and function or to actions by the immune system or other reactions.

The infusion of federal funding in Canada to explore the wide-ranging question posed by mitochondrial transplantation marks the first nationally funded initiative of its kind.

Discussion with Dr. Andreazza

MitoWorld: There seems to be a real divergence in the thinking in the scientific community of whether transplantation is real in terms of transplanted mitochondria taking up their full functions once transplanted. How do you and the team answer those questions?

Andreazza: Indeed, this divergence is a major reason our team has come together under the NFRF-Transformation grant. Rather than assuming one mechanism over another, our approach is to systematically evaluate how transplanted mitochondria interact with host cells, whether by integrating functionally, or by initiating signaling pathways that support recovery or regeneration. Using innovative tools such as live imaging, mitochondrial tagging, and 3D tissue models, we aim to directly observe and measure mitochondrial behavior post-transplantation.

MitoWorld: On the other hand, there is the fear that the patient communities, especially those who have mitochondrial genetic diseases or are parents of children who do, will have their hopes falsely raised in the short term. How do you and your team counsel the mitochondrial patient community at this point?

Andreazza: We are deeply aware of the responsibility we have to the patient community. Transparency is central to our approach. While mitochondrial transplantation holds promise, we are careful not to frame it as a near-term therapeutic option for genetic mitochondrial diseases. Instead, we emphasize that this is an early-stage scientific endeavor with an initial potential for ex-vivo organ regeneration. We engage with patient groups regularly. In fact, the MitoCanada Foundation was part of the design of the project from the beginning, and it is now forming patient and communities committee that will oversee the project development. Most importantly, listening to concerns and co-developing knowledge translation strategies are central to ensure expectations remain grounded in the realities of where the science currently stands.

MitoWorld: Where do you and the cross-disciplinary and cross-institutional team hope to focus first, and what solutions or findings do you anticipate?

Andreazza: Our first focus is to establish the mechanism that underlies mitochondrial transplantation. Using 3D tissue and animal models, we hope to determine how mitochondria survive transfer, how long they persist in recipient cells, what cells uptake mitochondria, and what outcomes they influence. We’re particularly interested in ex-vivo organ regeneration for improvement of organ transplant. From this foundational science, we hope to develop tools that can guide future clinical applications, including standardized protocols and safety metrics.

MitoWorld: It would seem that Canada is the first national government to make an investment in mitochondria transplantation. What do you think motivated decision from a policy, scientific, and treatment perspective?

Andreazza: Canada’s investment reflects the country’s forward-looking research framework that embraces high-risk, high-reward strategies. It aims to elucidate the roles of mitochondria in health and in nearly every major disease with an opportunity to transform our understanding, and hopefully treatment strategies. In my view, these opportunities made this a compelling story for support under the NFRF’s Transformation Stream. Additionally, the interdisciplinary and community-driven nature of the project aligns well with Canada’s emphasis on collaboration and innovation.