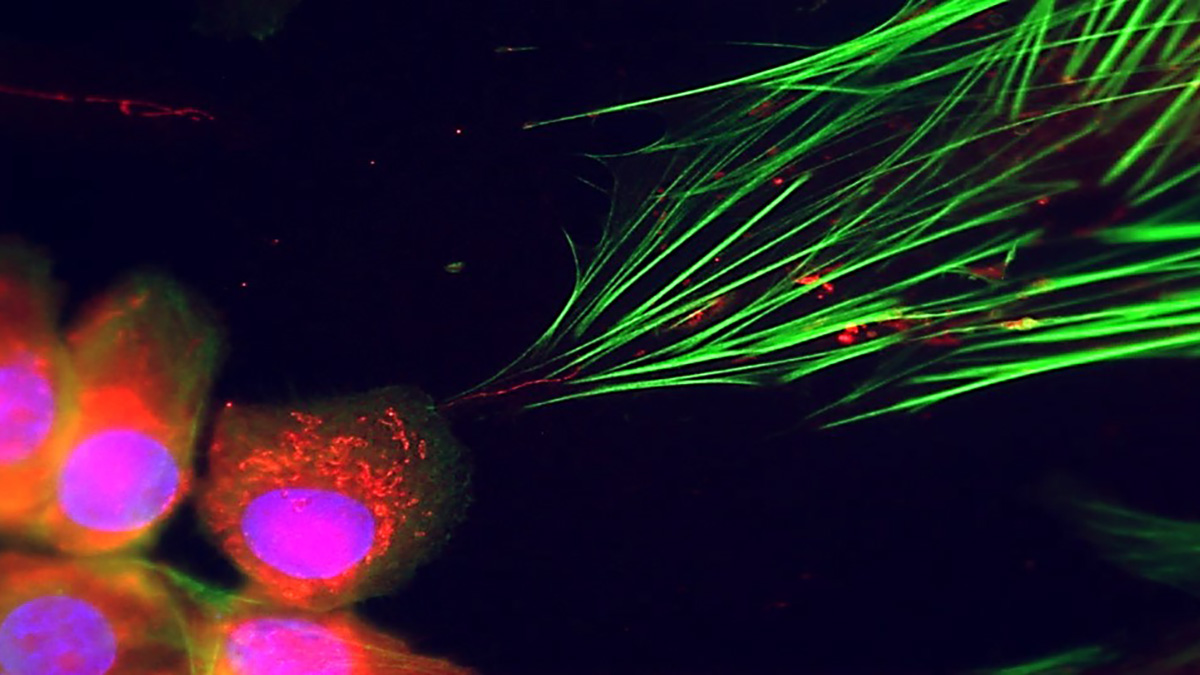

Host mitochondria (green) surround the Toxoplasma parasite (red).

Mitochondria Fight Pathogens by Starving Cells of Folate

Mitochondria Fight Pathogens by Starving Cells of Folate

In a recent paper in Science, a research team led by Lena Pernas of UCLA showed that cells infected with a pathogen activate their mitochondria to gobble up the available folate.

Mitochondria are deeply involved in cellular metabolism and use many of the nutrients that a pathogen need. Is this competition for resources simply a coincidence, or is it a strategy to protect against pathogens? The Pernas group focused on the replication of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which requires the materials for nucleotide biosynthesis. For a model pathogen, they used the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. For the parasite, folate is essential to make thymidine for DNA synthesis and proliferation.

Interestingly, the researchers found that the parasite caused the cells to begin making new mtDNA, which depended on the integrated stress response and its key effector, the activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4). They found that ATF4 turns on one-carbon metabolism, which requires folate, to increase mtDNA. They also noted that disrupting mitochondrial one-carbon metabolism resulted in increased parasite replication.

T. gondii needs folate to make thymidine and new DNA, but ATF4 activation short-circuits that synthetic pathway by depriving the pathogen of folate. They concluded that the cells actually use mitochondrial metabolism as a weapon against pathogens.

A Conversation with Dr. Pernas

MitoWorld: This is an interesting paper about how cells use mitochondria indirectly to defend against a pathogen. Can this phenomenon be generalized to other pathogens or other nutrients?

LP: I think so—especially for pathogens that depend on host nutrient that can be sequestered or consumed by host mitochondria.

MitoWorld: What might be the next steps in your research into this action?

LP: Our immediate next steps are to understand if we can pharmacologically enhance mito1C during infection to restrict parasite growth, and to define other ways mitochondria limit pathogen replication.

MitoWorld: Are there any harmful side-effects of using up a portion of the folate in the cell? LP: This is such an exciting question! Another way to think of it is: can mitochondria become ‘selfish,’ and limit critical nutrients for the cell? That’s a concept that Dr. Tania Medeiros (the first author) will explore in her lab. I don’t think transient activation of mito-1C has harmful side-effects. However, in cases of mitochondrial disease where mito-1C enzymes are chronically activated, this may harm the host cell by restricting folate needed for other processes—analogous to the limiting of dTTP by dysfunctional mitochondria from nuclear genome replication, as Anu Suomalainen-Wartiovaara (U. of Helsinki) has shown.

MitoWorld: Is the mtDNA made in response to the pathogen simply degraded?

LP: We don’t have any evidence for degradation. One puzzling result is that, although mtDNA levels increase, we don’t see a corresponding increase in mtRNA or mtDNA-encoded proteins. One possibility is that the parasite produces an effector that inhibits the translation of mtDNA-encoded proteins.

MitoWorld: Can you speculate on whether this phenomenon might be used therapeutically? LP: It might be difficult since folate is a critical vitamin for multiple processes. I can speculate that increasing folate concentrations may not be beneficial during infection. In fact, elevated serum folate has been associated with increased malaria parasitemia in humans. Plasmodium, the causative agent of malaria, is another parasite that relies on folate for dTMP synthesis. Rather, we should consider how to specifically enhance mito1C, or mitochondrial use of folate. Another point is that the inhibition of the ISR has been explored in different disease contexts, but if this blocks mito1C, it may be important to first test individuals for pathogen burden.

MitoWorld: How did you become interested in mitochondria in the first place?

LP: When I started graduate school, my PhD advisor (John Boothroyd, Stanford U) showed me an electron micrograph of a monocyte isolated from a mouse infected with Toxoplasma. I couldn’t stop thinking about why all the mitochondria of that cell were surrounding the parasite. I’ve been working on this question ever since!

Reference

Medeiros TC, Ovciarikova J, Li X, Krueger P, Bartsch T, Reato S, Crow JC, Tellez Sutterlin M, Martins Garcia B, Rais I, Allmeroth K, Hartman MD, Denzel Ms, Purrio M, Mesaros A, Leung K-Y, Greene NE, Sheiner L, Giavalisco P, Pernas L (2025) Mitochondria protect against an intracellular pathogen by restricting access to folate. Science 389(6761): eadr6326.