Soccer headings (sub-concussive head impacts) influence central TCA cycle metabolite levels. These effects are potentially modulated by ADHD psychostimulant medication.

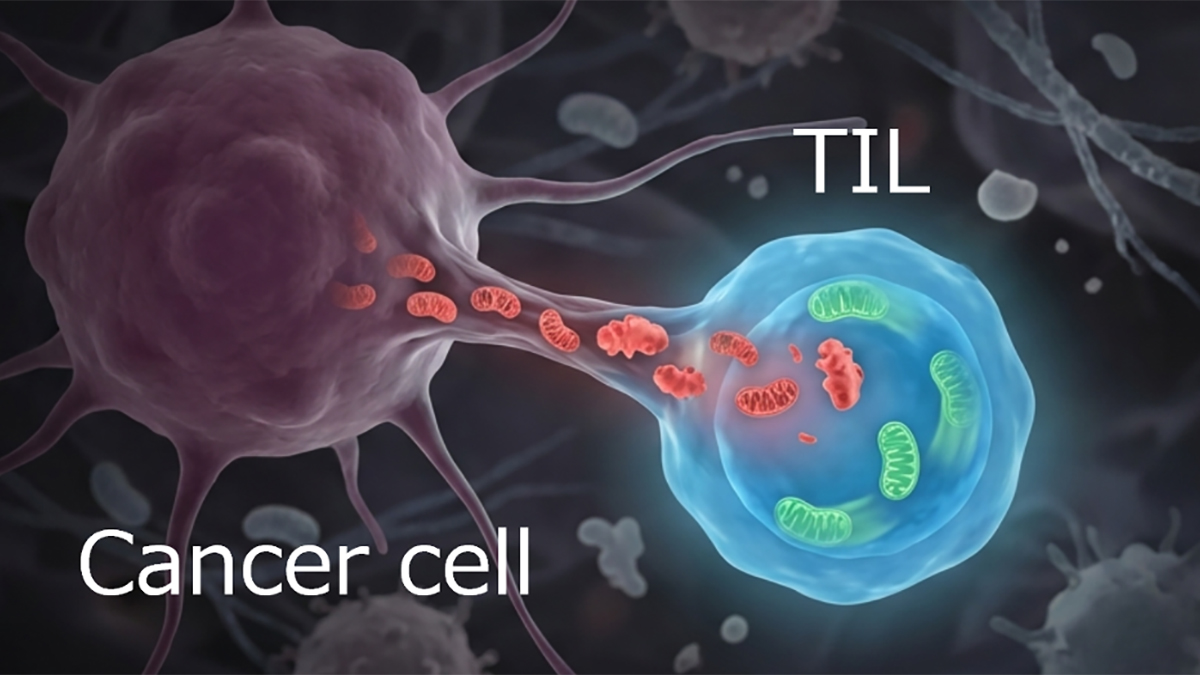

Mitochondrial Dysfunction after Repetitive Head Injuries

In a recent paper in iScience, an inter-institute research team led by Keisuke Kawata and his PhD student, Gage Ellis, examined the effects of repetitive head injuries in athletes with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). They found baseline levels of tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle metabolites were elevated in the ADHD group. After head injuries, both groups had lower levels, but the ADHD group had greater decreases. Thus, ADHD is associated with elevated baseline levels, but all athletes experience mitochondrial dysfunction after head injuries.

Athletes often suffer head injuries, and heading the ball is a common activity in soccer. The research team sought to determine the effects of subconcussive impacts of a normal soccer ball on mitochondrial function. They used a machine to launch a soccer ball at a specific speed to be headed by the player. Each player completed 10 headers. The researchers examined 25 players with and 25 players without ADHD by determined levels of TCA metabolites (e.g., oxaloacetate, citrate, isocitrate, pyruvate, alpha-ketoglutarate, and fumerate) in the blood before and after the head injuries.

Interestingly, they found that athletes with ADHD had elevated levels of citrate, isocitrate, malate, and oxaloacetate before the experiment. After the headers, both groups of athletes had lower levels, but the ADHD athletes had lower levels than the non-ADHD athletes. The ball impacts, although common in soccer players, had a significant effect on mitochondrial function.

These findings provide important insights into two key areas. While concussions have received a lot of attention in the last few years, players of other sports, such as soccer and basketball, are at risk for head injuries. Soccer is an extremely popular sport among young athletes these days. ADHD has become more common. Lower levels of citrate and oxaloacetate are assumed to indicate reduced energy production, and higher levels of the metabolites indicate increased energy demand. This study links mitochondrial dysfunction to both of these conditions and, in so doing, points to potential strategies to prevent or treat those injuries.

Discussion with Dr. Kawata and Mr. Ellis

MitoWorld: [Kawata] These findings are very relevant to the prevalence of ADHD and soccer among young people these days. Can you give us an indication of what direction your research might go in to advance these findings?

You’re absolutely right. Our findings have broad relevance beyond just soccer. Many athletes in contact sports experience repetitive head impacts, and brain energy metabolism is a key marker of healthy brain maturation and aging. Regarding ADHD, one important next step is to understand how psychostimulant medications might modulate the brain’s response to subconcussive impacts. We’re also very interested in exploring potential countermeasures for these head impacts, since we still don’t have an effective prophylactic agent that can truly enhance brain resilience against repetitive trauma.

MitoWorld: [Kawata] The injury model used in the experiment was much more mild than the injuries incurred in many contact sports. Do you have any plans to look at patients after more serious injuries?

I think the real novelty of our work lies in studying these more subtle impacts rather than the obvious, severe injuries. Cellular responses to major brain trauma have been explored for decades, but what’s fascinating is that even something as mild as 10 soccer headers can trigger dramatic changes in TCA cycle metabolites. That’s a completely new insight. So rather than moving toward more serious injuries, we plan to keep focusing on this subconcussive spectrum of brain trauma. It likely carries broader implications for athletes and everyday populations.

MitoWorld: [Ellis] Can you speculate on how ADHD might be linked to enhanced levels of mitochondrial activity as evidenced by the higher levels of those compounds?

The athletes with ADHD that participated this study were all ingesting prescribed ADHD medication. There are several different types of ADHD medication, the most common of which are stimulants. Psychostimulant ADHD medication functions by altering dopaminergic and adrenergic pathways, specifically at the postsynaptic cleft. By binding to dopamine and norepinephrine receptors, neurotransmitters released by the presynaptic cleft are then reabsorbed. It is possible that the extracellular level of neurotransmitters and increased binding of synaptic receptors could alter the ionic state of the cell, upregulating ATP demand and then in turn increasing metabolic demand prior to exposure to head impacts. Another potential link to increased energy metabolite levels at baseline would be ADHD stimulant medication’s role as an immunomodulator, in which it has been reported to increase brain-derived neurotrophic factor, as well as suppress inflammatory interleukins such as interleukin-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. In addition to modulation of pro and anti-inflammatory proteins, stimulant medication has shown to modulate oxidative stress as well, with evidence of both increasing and suppressing reactive oxygen species (ROS). While it is unclear the direction of modulation for ROS, it is notable that ADHD medication does play a role in oxidative stress and therefore could be the source of the enhanced mitochondrial activity denoted in this study.

MitoWorld: [Ellis] Can you envision a therapy for ADHD or head injuries that might involve treating mitochondria?

There are several different possible therapies for ADHD and for head injuries that include modulating mitochondrial function. One potential intervention would be pretreating with omega-3 fatty acids such as eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acid, which reduce oxidative stress and reinforce cell membrane structural integrity. Another potential therapy for head injuries, as well as ADHD, that also affect the mitochondria would be graded aerobic exercise. Currently, graded incline treadmill walking is a common protocol to treat concussions by reducing symptoms and improving return to play in athletes. Exercise improves ADHD symptom expression in children and adolescents, as well as reduces pro-inflammatory interleukins in individuals who engage in regular exercise. In addition to treating head injuries and improving ADHD symptom outcomes, aerobic exercise helps to regulate glycolytic pathways and improve metabolism.

In spite of all of this, the type of exercise, the intensity, and therefore the dosage for improving ADHD symptoms has not been defined and therefore is unknown. In addition to this, the graded incline treadmill walking to improve concussion outcomes is also extremely heterogenous per the individual.

MitoWorld: [Ellis] Did you have enough ADHD athletes in your study to see increase risk with those with more severe ADHD?

For this study, although we had 25 individuals with ADHD participate in the study, we did not see an increased risk correlated with ADHD severity. However, given the ADHD participants were all using medication, it is possible that ADHD severity and symptom expression was dampened, therefore making it improbable that ADHD severity would be correlated with mitochondrial outcomes.

MitoWorld: [Kawata] How did you come to be interested in mitochondria in the first place?

My interest in mitochondria actually goes back to my master’s program, when I worked in a lab focused on mitochondrial biology. I studied brain mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy, which really sparked my fascination with how these processes sustain neural health. More recently, I was part of a study (Vike et al., 2022, iScience 25(1):103483) that found potential links between head impacts and mitochondrial energy deficiencies in American football players. However, the causal relationship was still unclear because human studies at the time weren’t well controlled. That’s what motivated us to use a metabolomics approach in a rigorously controlled trial, to better understand how mitochondria respond to subtle head impacts.

Reference

Ellis G, Nowak MK, Kronenberger WG, Recht GO, Ogbeide O, Klemsz LM, Quinn PD, Wilson L, Berryhill T, Barnes S, Newman SD, and Kawata K (2025) Alterations in mitochondrial energy metabolites following acute subconcussive head impacts among athletes with and without ADHD. iScience 28(6).