December 12, 2025, Martin Picard, Mitochondrial Stress, Brain Imaging, and Epigenetics, “MiSBIE” Symposium

Mitochondrial Psychobiology Community Gathers at Columbia

Long associated only with energy and somewhat ignored, mitochondria are now recognized as key components in development and disease. On December 12, nearly 550 researchers met in person and virtually at Columbia University to assess the accomplishments and future directions of the Mitochondrial Stress, Brain Imaging, and Epigenetics—MiSBIE study. The study (Kelly et al. 2024) sought to understand the role of mitochondria and energy in mind-body processes and mitochondrial diseases. The “mother paper” (Kelly et al.), as they call it, also spawned other papers.

Symposium organizer Martin Picard (professor of behavioral medicine, Columbia) began by describing the holistic approach to the study. “We want to understand you as a person,” they emphasized to each study participant, as they welcomed them for the 2-day protocol in Manhattan.

Humans can be studied at various levels, including the molecular, cellular, tissue and organ, individual, and populations. The study sought to elucidate the interconnections of these levels through the lens of energy. More specifically, the MiSBIE team focused on the interactions of the immune system, mitochondria, the brain and nervous system, stress hormones, cognition, and behavior. Picard emphasized the importance of working as a team by noting the adage, “If you want to go quickly, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.” The discussions that followed featured several of his research group who contributed to the study.

Brain Mitochondria: The Energetic Landscape

In parallel with integrating mitochondrial energetics with psychobiology, the team developed the first mitochondrial map of the brain (Mosharov et al., 2025), a process led and described by Michel Thiebaut de Schotten (director of research, NeuroCampus of the University of Bordeaux). To link cognitive neuroscience and cell biology, they divided a frozen human coronal hemisphere section into 703 cubes or voxels (3 × 3 × 3 mm). Then, they defined the mitochondrial phenotypes (e.g., oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) enzyme activities, mitochondrial (mt)DNA and volume density, and mitochondria-specific respiratory capacity) in each voxel. The map revealed different characteristics for each region of the brain. If validated, the MitoBrainMap v1.0 of mitochondrial phenotypes might eventually allow exploration of the energetic landscape of normal brain function and correlations with standard neuroimaging methods—by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

“If this works, it would really be game changing,” said Picard. “You beam energy at the brain with a big magnet, then capture energy coming out of the brain, and somehow that tells you something about the biology of mitochondria. Amazing if this works.”

Building on the MiSBIE neuroimaging dataset, Tor Wager, PhD (professor of neuroscience, Dartmouth) and postdoctoral fellow Ke Bo examined behavioral and cognitive tasks through an energy-focused lens. One of their goals was to identify useful brain neurologic signatures associated with mitochondrial disorders. The molecules GDF15 and FGF21 show the strongest differences between individuals with mitochondrial disorders and controls. Wager used fMRI imaging to look for patterns in response to different tasks. These include cognitive (working memory, executive function tests), affective (cold pain), and sensory (multisensory with lights and stresses). Some of the correlations to mitochondrial disorders include sensitivity to negative emotions, but not to heat. In summary, the team finds that some brain functions and neural circuits are selectively vulnerable to energy deficits (Bo et al. Biorxiv 2025), consistent with an energy tradeoffs or “triage” model of psychopathology.

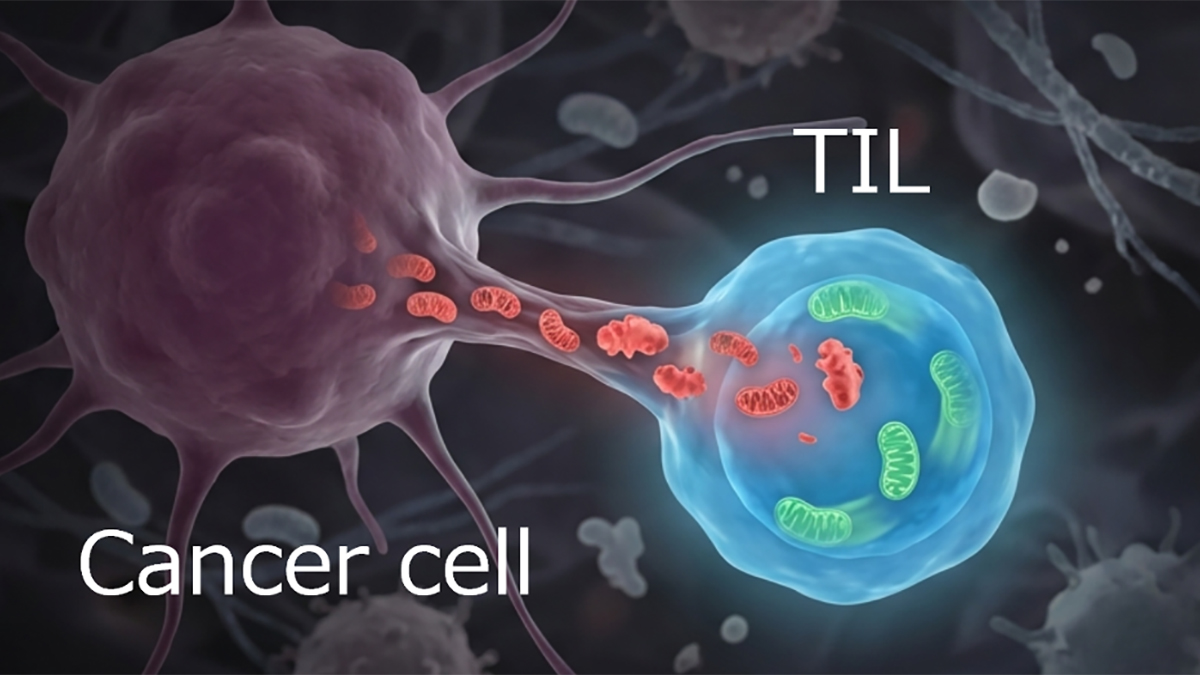

Immune Cell Bioenergetics

The group then wanted to examine the bioenergetics of immune cells. Jack Devine described how they stratified the phenotypes (or mitotypes) of immune cells. He used a new method developed by Anna Monzel, called mitotyping. Using principal component analysis, hierarchical clustering, and downstream analysis, they analyzed single immune cells from 164 people (ages 26–84). The MiSBIE team found that different types of immune cells have distinct patterns of activity (e.g., OxPhos, glycolysis) and aging.

To measure the bioenergetics of those cells from individuals with mitochondrial disorders, the group used extracellular flux analysis (Seahorse). Anna Monzel explained the process in beautiful details. The MiSBIE team isolated blood cells—monocytes, lymphocytes, neutrophils, platelets—from fasting individuals. For each cell type, they then measured their oxygen consumption and extracellular acidification rates to estimate OxPhos and glycolytic activities, using drugs that block specific enzymes in the mitochondria. OxPhos capacity was reduced in some cell types (not all) in people with mitochondrial disorders, but glycolysis was largely unchanged.

Using a biochemical approach called the mitochondrial respiratory capacity (MRC, formerly the Mitochondrial Health Index, MHI), Cynthis Liu examine mitochondrial biology in the same cells, of the same MiSBIE participants. She then used these data to explore the psychobiological relationships of immune cell mitochondria and mood symptoms, including anxiety and depressive symptoms. The work focused on mitochondrial respiratory chain at complexes I, II and IV, citrate synthase, and mtDNA content. The conclusion was that the maximal energetic capacity of immune cells is largely intact in mitochondrial diseases. Immune mitochondria are thus unlikely to reflect mitochondrial energetics in other tissues, such as the brain, muscles, and other organs.

Health Indicators: Time Perception

The MiSBIE study then focused on the indicators of health for those with mitochondrial disease. Two of these are the perception of time and allostatic load. Darshana Kapri examined the relationship of mitochondria to time perception. Individuals perceive time differently. Some people’s internal clocks run faster or slower than the actual time. Mitochondrial disorders didn’t directly affect time perception (faster or slower) but seemed to affect how potential drivers of time perception, including stress/metabolic hormones, such as norepinephrine, or metabolic rate. The team also discovered potentially meaningful associations between symptoms of burnout and fatigue and time perception, which demand validation in future studies.

Alex Junker then looked at allostatic load—a multi-system metric of physiological dysregulation known to predispose to disease. Allostatic load was higher in people with mitochondrial diseases and strongly correlated with lifetime stress and trauma. So genetics is important, but those with disease might be affected by their lived environment and the psychosocial factors that surround them. This new knowledge could motivate interventions or approaches that can provide additional support for those who have mitochondrial diseases.

Energetics of Stress: Cell-Free Mitochondria

The study also focused on the energetics of stress. Natalia Bobba-Alves described how the group developed a stress reactivity protocol and the effects of mitochondrial disorders. That protocol, which included eight concurrent blood and saliva collection timepoints over a 2-hour period, was used to study several stress mediators. The main stressor was a 5-minute speech task where participants had to give a speech in front of a white coat-wearing intimidating evaluators, while being (mock) videotaped.

David Shire explained their work on cell-free mtDNA in saliva and blood and stress. Levels of cell-free mtDNA are elevated in patients with cancer, heart disease, and inflammation. Higher levels of cf-mtDNA were detected in saliva than in serum or plasma from the same person. Stress caused a nearly 10-fold elevation in saliva cf-mtDNA within 10 minutes on average.

Mangesh Kurade presented results on FGF21 levels after the same stressor. The levels are significantly elevated in people with mitochondrial disorders. They decrease from morning to afternoon, and tend to be higher in people with higher body fat and in older people. Mental stress decreased plasma FGF21 in most control individuals, whereas it caused a robust increase in people with mitochondrial disorders—a remarkable divergence.

Caroline Trumpff looked at whether mental stress altered the mitochondrial disease biomarker GDF15. This molecule is the most robust available marker of mitochondrial disorders and energetic stress. The MiSBIE team found that psychological stress alone is sufficient to causes GDF15 levels to rise, both in blood and in saliva. This new discovery links mental and energetic stress, suggesting that both might converge on mitochondria and reductive stress, the key trigger for GDF15 release.

Future Directions: Hypermetabolism and mtDNA Instability

Evan Shaulson covered an ambitious follow up study: the Mitochondrial Daily Energy Expenditure (MDEE) study. Individuals with OxPhos defects often have fatigue and a short lifespan—on average reduced by 3-4 decades. Evan Shaulson described in vitro experiments from Gabriel Sturm on patient-derived fibroblasts, where subjecting cells to conditions that disrupted OxPhos doubled cellular energy expenditures. This state of hypermetabolism was associated with mtDNA instability, activation of the integrated stress response, and secretion of age-related cytokines and metabokines.

In the new MDEE study (manuscript in preparation), additional experiments were conducted with volunteers who spent a day in a small room while their metabolic rates, activity levels, and other psychobiological parameters were carefully and continuously measured. Half of the volunteers had a mitochondrial disease, and the other half were healthy controls—as in MiSBIE. For a further 8 days, MDEE participants lived their normal lives. The study found that like the fibroblast experiments, individuals living with OxPhos defects experience hypermetabolism. Thus, in both isolated cells and people, mitochondria with defects result in hypermetabolism and reduced lifespan, the connection between which remains to be better understood. This may relate, as the team proposes, to energy constraints that force deleterious tradeoffs where stress-related processes compete with health and healing-promoting processes.

Martin Picard summed up the symposium by focusing on a major gap in knowledge: “Healing is a set of dynamic, energetic processes by which an organism moves towards optimal function. Healing involves growth and development, recovery from injury, and adaptation that increase coherence and efficiency across the organism. Although healing is most likely the key driver of health, and the basis for not getting sick in the first place, we don’t have a science of this. We need a science of healing,” he said, pointing to their work around the science of health, and a new initiative to be unveiled in the coming year.

“Rational, scientific ways to harness the healing process would likely lead to new treatments and interventions that help optimize mitochondrial energy transformation. That would likely then contribute to more coherent and efficient psychobiological processes, freeing up energy to fuel the healing process and sustain health across the lifespan.”

The MiSBIE Symposium concluded with a reception that celebrated the scientific success of the NIH-funded study, supported by Baszucki Group. “MiSBIE sets the table for a new phase in the evolution of health sciences. Understanding psychobiological processes at an energetic level provides a foundation to develop a true science of healing: Healing Science,” said Picard. “There is a lot to be excited about. And we need everyone on board, not just scientists, to come along and join the movement.”

References

Kelly C, Trumpff C, Acosta C, Assuras S, Baker J, Basarrate S, Behnke A, Bo K, Bobba-Alves N, Champagne FA, Conklin Q, Cross M, De Jager P, Engelstad K, Epel E, Franklin SG, Hirano M, Huang Q, Junker A, Juster R-P, Kapri D, Kirschbaum C, Kurade M, Lauriola V, Li S, Liu CC, Liu G, McEwen B, McGill MA, McIntyre K, Monzel AS, Michelson J, Prather AA, Puterman E, Rosales XQ, Shapiro PA, Ghire D, Slavich GM, Sloan RP, Smith JLM, Spann M, Spicer J, Sturm G, Tepler S, Thiebaut de Schotten M, Wager TD, Picard M, The MiSBIE Study Group (2024) A platform to map the mind–mitochondria connection and the hallmarks of psychobiology: The MiSBIE study. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism (10): 884–901.

Mosharov EV, Rosenberg AM, Monzel AS, Osto CA, Stiles L, Rosoklija GB, Dwork AJ, Bindra S, Junker A, Zhang Y, Fujita M, Mariani MB, Bakalian M, Sulzer D, De Jager PL, Menon V, Shirihai OS, Mann JJ, Underwood M, Boldrini M, Thiebaut de Schotten M, Picard M (2025) A human brain map of mitochondrial respiratory capacity and diversity. Nature 641: 749–758.

Sturm G, Karan KR, Monzel AS, Santhanam B, Taivassalo T, Bris C, Ware SA, Cross M, Towheed A, Higgins-Chen A, McManus MJ, Cardenas A, Lin J, Epel ES, Rahman S, Vissing J, Grassi B, Levine M, Horvath S, Haller RG, Lenaers G, Wallace DC, St-Onge M-P, Tavazoie S, Procaccio V, Kaufman BA, Seifert EL, Hirano M, Picard M (2023) OxPhos defects cause hypermetabolism and reduce lifespan in cells and in patients with mitochondrial diseases. Communications Biology 6(1): 22.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s42003-022-04303-x.pdf