Mitochondrial Transfer Leads to Immune Evasion by Cancers

Recently, a multi-institute research team led by Yosuke Togashi reported on a study that showed that cancer cells transfer mitochondria with mutant DNA and inhibitory molecules to immune cells to reduce the antitumor response. This previously unknown mechanism also shows that cancer cells with mutated mitochondrial (mt) DNA indicate a poor prognosis for certain patients.

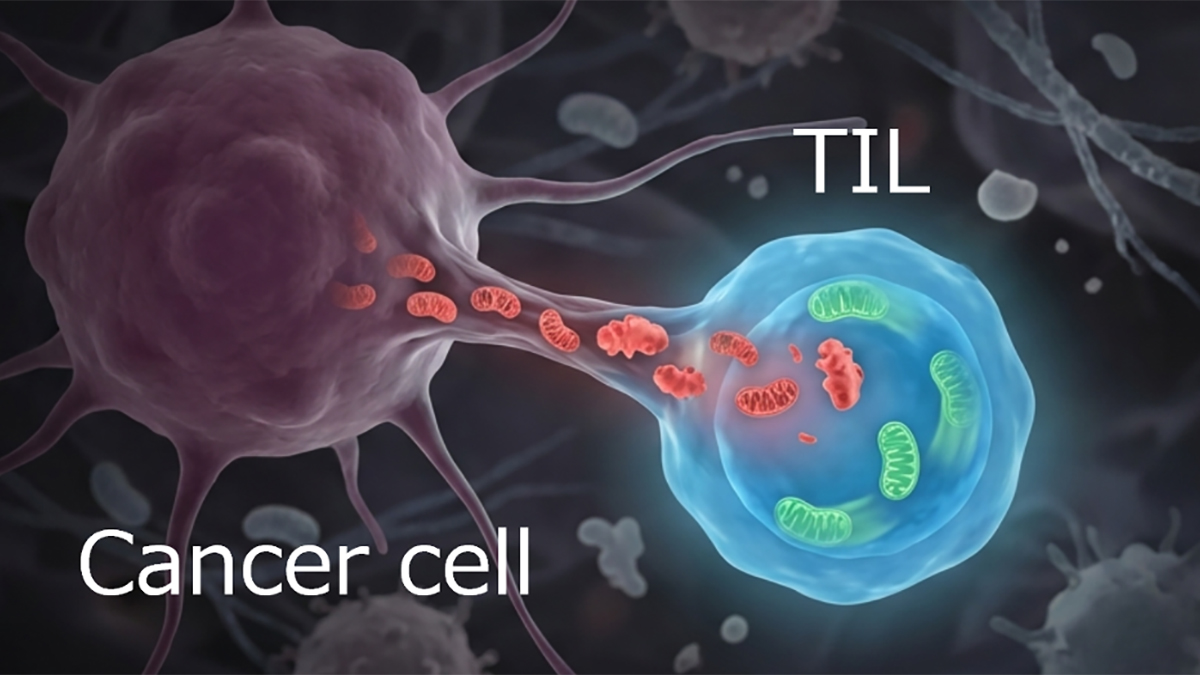

Cancers use many strategies to avoid immune surveillance. Among those are the acquisition of mitochondria from T cells that infiltrate the tumor. Those mitochondria enhance the cancer cells energy production. But the transfer of mitochondria also works in the other direction. Mitochondria with mutations from the cancer cells are transferred to the immune cells. Those defective organelles degrade the antitumor response. Thus, the metabolic reprogramming resulting from the bidirectional exchange of mitochondria creates an environment that encourages tumor growth.

The Togashi research team sought to determine the mechanisms that promote that exchange. They examined clinical samples of immune cells for mtDNA mutations from the cancer cells. They found similar mutations in mtDNA in the immune cells. In most cases, mitochondria with mutated mtDNA are destroyed by mitophagy. However, the team identified proteins that attach to the mitochondria with mutated mtDNA and are transferred with them to the immune cells. One of these was the mitophagy-inhibiting protein USP30. Those recipient immune cells then failed to undergo mitophagy. In addition, the T cells with the mutant mitochondria became senescent.

This work has valuable clinical implications. Finding of mutant mtDNA in the cancer cells indicates that immune checkpoint inhibitors may be less effective in patients with melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer.

A conversation with Dr. Togashi

MitoWorld: What directions do you foresee your research taking to advance this work?

Togashi: Our next steps are to clarify the mechanistic basis of mitochondrial replacement in addition to just transfer, the key molecules on donor and recipient cells, and the tumor microenvironmental conditions that promote it. We will then expand the work across additional cancer types and other recipient cell populations (beyond T cells) to build a broader map of who transfers mitochondria to whom and with what functional consequences. We are also interested in whether similar mitochondrial transfer in non-cancer diseases, such as chronic inflammation disease. In parallel, we will determine how transfer intersects with mitochondrial dynamics (fusion-fission, mitophagy, and quality control) that may determine whether transferred mitochondria persist. Ultimately, we aim to translate these findings into biomarkers that predict therapy response and therapeutic strategies that restore mitochondrial quality control to improve immunotherapy efficacy.

MitoWorld: Do you have any thoughts on the mechanism by which the immune cells receiving the mutated mtDNA become senescent?

Togashi: We think senescence is likely driven by a combination of mitochondrial dysfunction and stress signaling. Mutant mitochondria can impair respiratory capacity and elevate reactive oxygen species, which may trigger DNA-damage responses and activate pathways, such as p53–p21 and/or p16. Importantly, if mitophagy is suppressed, these damaged organelles may persist, making the dysfunction more durable.

MitoWorld: As you noted, mitochondria might be mediated by various mechanisms. Do you have a favorite candidate for this process?

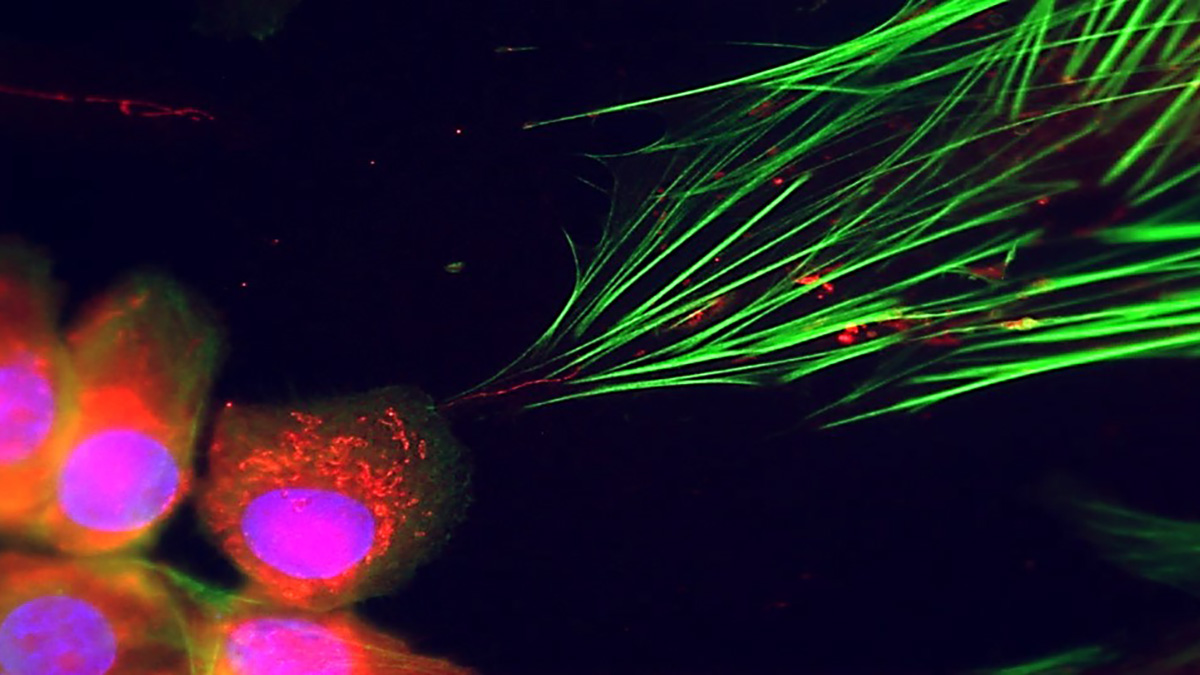

Togashi: Several mechanisms could plausibly mediate mitochondrial transfer, including tunneling nanotubes, extracellular vesicles, and direct cell-cell contact-dependent processes. From our observations so far, a leading candidate is tunneling nanotubes and/or EVs. At the same time, we have the impression that the dominant route may differ, depending on the cell type and context. So these mechanisms are not mutually exclusive and may operate in parallel in different tumor microenvironments.

MitoWorld: Your work here and that of others have provided good evidence for the concept of mitochondrial transfer. However, some researchers have been slow to warm to this idea. Can you speculate on why there has been this reluctance to accept this?

Togashi: I think the hesitation is understandable. Demonstrating mitochondrial transfer convincingly in vivo is technically challenging: mitochondria are abundant, dynamic, and easy to mis-attribute due to imaging limitations, labeling artifacts, or contamination during cell isolation. In addition, the field has long emphasized mitochondria as strictly cell-autonomous organelles, so the conceptual shift takes time. In our case, we view the evidence as particularly strong because we can identify transferred mitochondria by shared genetic mutations in both clinical specimens and in vivo models, providing an orthogonal line of support beyond imaging alone. As methods improve, particularly lineage tracing, spatial approaches, and rigorous controls, I expect the evidence base will continue to strengthen and the community will converge.

MitoWorld: Do you have any speculation on how your findings might be translated to clinical applications?

Togashi: We see a few translational opportunities. First, tumor mtDNA mutation profiles could serve as biomarkers to stratify patients who are less likely to benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors and, thus, help to guide treatment selection. Second, therapeutically targeting the transfer process or restoring mitochondrial quality control in recipient immune cells may help to preserve anti-tumor immunity. Third, these insights may inform combination strategies (e.g., pairing immunotherapy with mitochondria-targeted agents), thereby converting non-responders into responders.

MitoWorld: How did you become interested in mitochondria?

Togashi: My original training is in pulmonary medicine and thoracic oncology. From there, I became increasingly interested in cancer immunology, and during my postdoctoral period, I worked primarily on regulatory T cells. I was already aware of the accumulating evidence that mitochondrial dysfunction is an important feature of exhausted T cells, but when I was preparing to start my own laboratory, I was searching for an original research direction. Around that time, I learned about the phenomenon of mitochondrial transfer, and it immediately struck me as a fascinating and potentially transformative concept for understanding tumor-immune interactions. That was the starting point that led me to pursue this line of work.

Reference

Ikeda H, Kawase K, Nishi T, Watanabe T, Takenaga K, Inozume T, Ishino T, Aki S, Lin J, Kawashima S, Nagasaki J, Ueda Y, Suzuki S, Makinoshima H, Itami M, Nakamura Y, Tatsumi Y, Suenaga Y, Morinaga T, Honobe-Tabuchi A, Ohnuma T, Kawamura T, Umeda Y, Nakamura Y, Togashi Y (2025) Immune evasion through mitochondrial transfer in the tumour microenvironment. Nature 638: 225-236.