Old Mitochondria Are a Factor in Cell Fate Decisions

In a paper1 published in Nature Metabolism, a research group at the University of Helsinki led by Pekka Katajisto, examined the effect of organelle age on cell fate determinations in tissues. Interestingly, they found that asymmetric cell divisions concentrate older mitochondria in stem cells that are more efficient in tissue renewal.

Specifically, the team sought to test the hypothesis that metabolism is a major factor in cell fate decisions and regeneration. They studied mouse intestinal stem cells (ISCs) that inhabit the crypts in the intestine where new intestinal epithelial cells are created to replace those normally worn out. They developed methods to isolate ISCs, based on the age of their mitochondria.

They were particularly interested in a subset of ISCs enriched with older mitochondria. While many other characteristics of this subset were similar to other ISCs, they did have some intriguing aspects. They form organoids more readily, which is consistent with their ability to reform their niche cells, thus leading to better resistance to damage by chemotherapy. They produce more a-ketoglutarate (aKG) that has many activities, including the ability to change epigenetics.

In summary, they found that in ISCs the aged mitochondria regulate cell fate. The findings suggest future treatment strategies that target the found metabolic mechanisms.

A Discussion with Dr. Katajisto

MitoWorld: What do you see as the next steps in your work? For example, you suggest that epigenetic changes (e.g., with aKG) might drive this process. Do you plan to look at that possibility?

Yes, we do already know that the process is dependent on epigenetic modifiers of the TET group of enzymes that hydroxymethylates methylated cytosines in the DNA. Interestingly, out of the relatively small set of genes with changes in this mark in ISC with old mitochondria, surprisingly many have been linked to processes related to regeneration or niche cell differentiation. We are currently probing if hydroxymethylation of these genes is crucial for the first steps of fate determination as ISCs become niche cells.

MitoWorld: Your paper suggests some fascinating possibilities. Can you speculate on the mechanism that allows the older mitochondria to be segregated during cell division? Is the relative success of cells with older mitochondria determined purely by energy needs?

The answer is that we don’t know yet. Somehow the cell must be able to recognize domains of the mitochondrial network based on their age as they enter mitosis. In our previous work2 using human asymmetrically dividing cell lines, we saw that older mitochondria localize closer to the nucleus. But how they are recognized and asymmetrically segregated in the cell we don’t yet know. We don’t think the intestinal stem cells with older mitochondria necessarily produce more energy in the form of ATP, as their morphology is not consistent with having higher oxidative phosphorylation capacity. However, again in our previous work3 we did see that older mitochondria in cultured cells have higher oxphos capacity. In the ISCs it seems to be instead the relative amount of the TCA intermediates aKG, succinate and 2-HG, which are crucial for the success of ISCs with old mitochondria in generating niche cells faster, and subsequently regenerate the epithelium.

MitoWorld: It has been hypothesized that aging began from the asymmetric division in bacteria. It is interesting that mitochondria, which derived from bacteria, have continued this practice in other settings. Is this as common a phenomenon as it might seem?

Katajisto: What a fascinating question. Although we have not looked into this it is quite possible that some of the mechanisms allowing of segregation of mitochondria of different age could be common to their bacterial ancestors, as are many other features of mitochondria. In any case, the discovery of seemingly separate sub-pools of mitochondria that are also selectively and asymmetrically segregated in cell divisions, raises interesting questions also for example on regulation of fission and fusion dynamics of mitochondria.

MitoWorld: The reprogramming of cells to iPSCs and other cell types has become routine in labs and showed the plasticity of cell fate commitments. Any thoughts on how mitochondrial aging and segregation fares in those protocols?

Katajisto: It is indeed interesting to look into this phenomenon in many iPSC-derived differentiations as introduction of our construct is relatively straightforward. However, the high amount of growth factors and inhibitors used in the in vitro differentiation protocols to force specification of certain lineages and cell fate may override naturally occurring subtle mechanisms, such as the metabolism imposed by age-selective mitochondrial segregation. We are currently looking for example into how mitochondrial age impacts the functional maturity of PSC derived pancreatic beta cells.

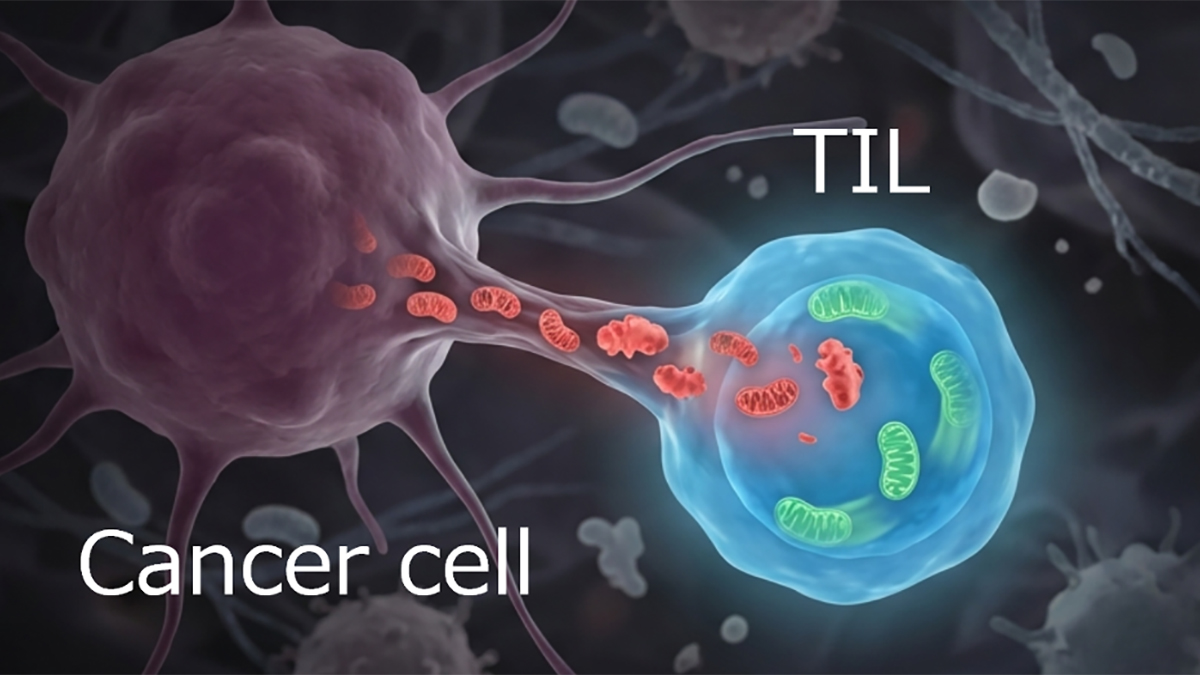

MitoWorld: This is an important finding for science. Can you see any treatment possibilities down the road? For example, might aKG supplementation be helpful? Or on a more speculative note, if the cell-to-cell transfer of mitochondria can be mastered, might those transfers be beneficial?

Katajisto: In our work, we found that giving aKG to old mice for 2 weeks before administration of the commonly used chemotherapeutic drug 5-FU promoted their recovery after the treatment known to cause severe side effects particularly in elderly patients. Thus, we think that aKG administration indeed has potential in chemoprotection, but we of course have to first test how aKG impacts the effectiveness of the drug against cancer. Mitochondrial transfer is another fascinating avenue, and it might well be that the differentiation potential or fitness of cells that are to be used for cellular therapy could be boosted with the transfer of the right kind of mitochondria. However, the effect from transferred mitochondria would probably be very transient, and so strategies targeting or mimicking the age-specific traits of mitochondrial metabolism by other means are likely going to be more practical.

Katajisto: MitoWorld: What drew you to the study mitochondria in the first place?

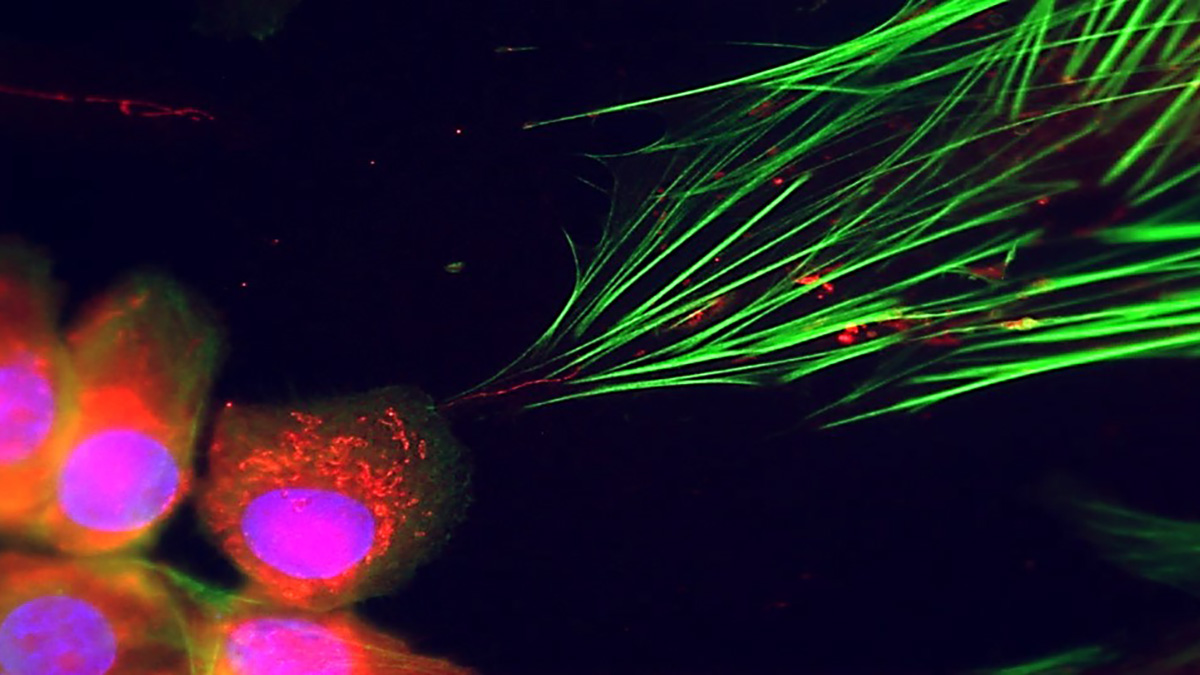

Originally,2 I set out to study if age-dependent segregation of organelles is a feature of mammalian asymmetrically dividing cells with the thought that stem cells might push the older, possibly damaged organelles, into the differentiating daughter cell to keep the stem cell pool healthy. Mitochondria3 and peroxisomes4 were found to be asymmetrically segregated between the differentiating and self-renewing daughter cells, but it turned out that old organelles were not damaged, just metabolically different. Thus, I started studying mitochondria because they were the most striking age-dependently segregated organelle in my original findings, using the human cell line, and it turned out that this was also taking place in tissue resident stem cells in mice.

References

1Andersson S, Bui H, Viitanen A, Borshagovski D, Salminen E, Kilpinen S, Gebhart A, Kuuluvainen E, Gopalakrishnan S, Peltokangas N, James M, Achim K, Jokitalo E, Auvinen P, Hietakangas V, Katajisto P (2025) Old mitochondria regulate niche renewal via α-ketoglutarate metabolism in stem cells. Nat Metab 7: 1344–1357.

2Katajisto P, Döhla J, Chaffer CL, Pentinmikko N, Marjanovic N, Iqbal S, Zoncu R, Chen W, Weinberg RA, Sabatini DM (2015) Asymmetric apportioning of aged mitochondria between daughter cells is required for stemness. Science 348: 340–343.

3Döhla, J., Kuuluvainen, E., Gebert, N. et al. (2022) Metabolic determination of cell fate through selective inheritance of mitochondria. Nat Cell Biol 24: 148–154.

4Bui, H., Andersson, S., Sola-Carvajal, A. et al. (2025) Glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase on old peroxisomes maintains self-renewal of epithelial stem cells after asymmetric cell division. Nat Commun 16: 3932.