Moving from Rhetorical and Evidentiary Stances to Tracking the Research

A Divided Community

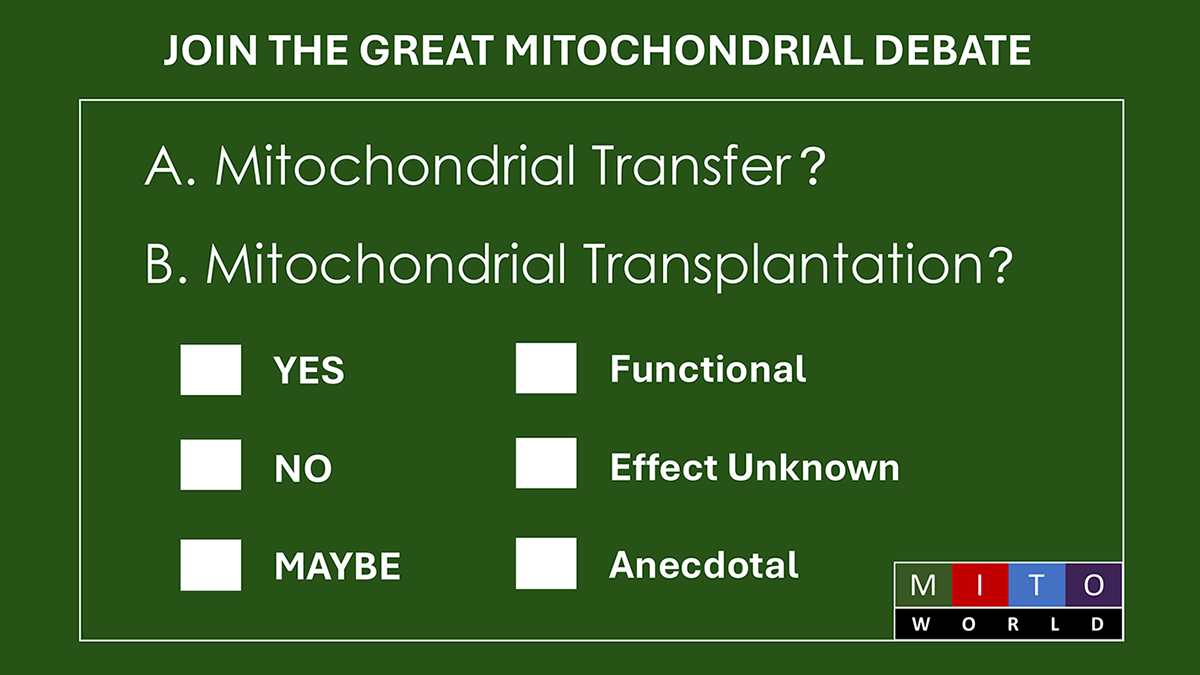

In a September 2025 Viewpoint published in Nature Metabolism entitled “Mitochondria Transfer,” the editors noted, “. . . the topic continues to be met with skepticism.” As a result, the journal asked nine mitochondrial biologists to share their personal views on intercellular mitochondria transfer. There was little new here.

Their responses amounted to yes, no, and maybe. Many questions loom for otherwise promising results. What are the mechanisms and consequences of this process? If mitochondria do move between cells endogenously, when they arrive in another cell, do they resume their normal functions? Does the transfer of a relatively small number of mitochondria have the power to rescue a cell that is under bioenergetic stress?

At MitoWorld, we know most of the Viewpoint respondents, and we know the gulf between them. By kicking off debate, Nature Metabolism has started a process that we hope can mature from rhetoric to a more evidence-based picture of the efficacy of mitochondrial transfer and transplantation. Across the globe, investigations are underway in both categories. Given the limited mechanistic understanding of this process, it is surprising that mitochondrial transplantation is now a not uncommon medical intervention and remains a tantalizing subject of research and development in a variety of biotech companies.

First Step: Nomenclature

In all of this, there is a blurring of terminology. In January, Jon Brestoff and Keshav Singh, et al. published “Recommendations for mitochondria transfer and transplantation nomenclature and characterization,” also in Nature Metabolism. What is clear in their paper’s title is the notion of i) transfer being endogenous, part of an intrinsic biological mechanism and ii) transplantation, the act of deliberately introducing mitochondria into organs, tissues, and cells being exogenous. Over 30 researchers participated in what was a laudable effort to explore agreed-upon naming, processes, and explanatory conventions. While the consensus statement and an agreement for an International Committee on Mitochondria Transfer and Transplantation Nomenclature (ICMTTN) represents an important step forward, notable disagreements persist. Foremost among the complications related to mitochondrial transfer and transplantation relates to the unknown fate of any mtDNA harbored by incoming organelles.

Second Step: Conference

MitoWorld found itself in the middle of this controversy when it was asked to help with the first Mitochondrial Transplantation Conference. Held in April at Hofstra University, the event was organized by Northwell Health and led by Lance Becker. It featured a mix of compelling medical intervention talks and video for failing hearts (James McCully), treatment for stroke victims (Melanie Walker), and other resuscitation experiments with animals (Lance Becker). MitoWorld assisted in having endogenous transfer represented (Jonathan Brestoff). In all of this, there was excitement but also apprehension that parents of children and adults with mitochondrial genetic diseases will be given false hope for near-term treatments. Several drug developers were present, as were patient groups. It is likely some form of transplantation organization will emerge from that meeting.

Deeper Dive—Transfer and Transplantation

Given the lack of evidence-based dialogue, MitoWorld reached out to the Viewpoint respondents who are actively doing work in both categories. Yasemin Sancak, The Sancak Lab, University of Washington Pharmacology, and Rubén Quintana-Cabrera, Neurometabolism and Mitochondrial Dynamics Lab, Instituto Cajal, CSIC responded to MitoWorld.

MitoWorld: Why do you think there is such a controversy about mitochondria transfer and transplant?

Sancak: Transfer of mitochondria between cells is shown in different organisms and systems, and although this is relatively novel finding, it is widely accepted in the field. However, mitochondria transplantation attracts skepticism. In my opinion, the controversy stems from the expectation that, for mitochondrial transplantation to work as intended, the transplanted mitochondria should successfully incorporate into the host tissue in large numbers and maybe survive there for a long time, integrate into the donor tissue, and restore mitochondrial function and tissue health. Currently, the evidence of this happening is limited, and mechanisms of mitochondrial entry and survival are not well understood. But we also cannot ignore the exciting data that show the utility of mitochondrial transplantation in the clinic. Until we understand the molecular details and mechanisms of this process, the controversy is likely to continue. The field needs more preclinical and clinical research to understand mechanisms of therapeutic benefit and to establish clinical guidelines.

Quintana-Cabrera: These are quite novel concepts, now widely accepted by the scientific community after solid data in different cells and tissues. My perception is that both general and even specialized audiences are mostly focused on the incorporation of healthy mitochondria from neighboring cells or tissues to enhance mitochondrial activity in the compromised recipient cell. However, we should not overlook the transfer of damaged mitochondria, which may also benefit a cell by enabling their elimination through surrogate degradation in neighboring cells. Regarding transplants, the apparent controversy mainly concerns the injection of isolated mitochondria. Transplants using donor cells, such as mesenchymal stem cells or mitochondria encapsulated in vesicles or artificial membranes are viewed as able to better withstand the extracellular environment and the journey through the body to the target tissue. However, those advocating for transplants of isolated mitochondria need to standardize the approaches and to clarify how mitochondria survive outside the cell, influence inflammation, and integrate into recipient cells, or if they can take over native mitochondrial function in the long term.

MitoWorld: What may convince you that transfer happens naturally and/or that transplantation has effects?

Sancak: Many animal and cell culture studies show that mitochondrial transfer happens naturally, and this process is likely to serve different functions. Mitochondrial transplantation research in a pre-clinical setting mostly shows positive outcomes, but the long-term benefits of mitochondrial transplantation are not addressed. A small number of human studies show clinical benefit, but these are mostly feasibility and safety studies that were conducted with a small number of patients. One promising common finding from human studies so far is that mitochondrial transplantation does not seem to have any adverse effects and is generally considered to be safe. I think this is very promising and should open the door to bigger clinical trials. Ultimately, well-controlled clinical trials are needed to determine if mitochondrial transplantation will work for a disease of interest and what long term effects will be.

Quintana-Cabrera: A growing body of evidence demonstrates the natural occurrence of different types of transfer, mediated by tunneling nanotubes, microvesicles, or naked mitochondria, across various tissues and both in physiology and pathology. This is leading the scientific community to accept mitochondrial transfer as a naturally occurring event.

Of course, this is still a young field, and existing gaps need to be addressed by thoroughly evaluating the various dimensions of mitochondrial transfer. For example, further progress is needed in the assessment of intercellular communication mechanisms, such as tunneling nanotubes, which contribute to mitochondrial transfer but are technically challenging to study in vivo. Transplantation can produce meaningful effects, at least in the short term, depending on the delivery method, dosage, and source of mitochondria. Additional manipulations may enhance mitochondrial integration, modulate immune responses, or improve targeting to the appropriate tissue. However, it remains essential to understand how transplanted mitochondria interact with a much larger population of resident ones and to characterize both the short- and long-term effects of transplantation. This knowledge will help determine which strategies are truly beneficial. Such benefits may arise from whole mitochondria, their components, or even from transient cellular responses triggered by the presence of exogenous mitochondria.

MitoWorld: What do you say to those who contend that transplantation, at best, is a reaction to the presence of transplanted mitochondria, not that transplanted mitochondria are functionally integrated into recipient cells?

Sancak: This is an important question that highlights the significance of understanding what happens at the molecular level once the external mitochondria are delivered to the recipient cells. Most animal experiments show that the transplanted mitochondria must be functional to provide a positive outcome in the recipient cells. This suggests that the recipient cells’ reaction to presence of transplanted mitochondria is not the whole story, and transplanted mitochondria function is important. I think it is more likely that both mechanisms will play a role, and depending on the disease, transplantation method, and recipient cell, one mechanism may play a more prominent role than the other.

Quintana: This is a critical question that indeed needs clarification. Are transplanted mitochondria directly restoring function, or are they instead exerting indirect effects that still benefit the recipient cell or tissue? The latter could involve activation of stress-response pathways that partially restore homeostasis. Again, the source or method to deliver mitochondria may be key to what response is engaged, and the functional integration of mitochondria may not always be necessary to explain beneficial outcomes. Depending on the kind of transfer, whole mitochondria, or at least mitochondrial DNA, may escape degradation and integrate into the acceptor cell. Even in this scenario, we still need to assess whether and how their contribution reconfigures the native mitochondrial content, and what other events may occur in parallel.

MitoWorld: What does your research from actual cases tell you about what the transplanted mitochondria are actually doing?

Sancak: The transplantation studies I was involved in were focused on safety, and no clinical outcomes other than safety were monitored rigorously. What I can say is that mitochondrial transplantation appears safe in every system tested, which makes it more appealing to pursue as a potential therapeutic intervention. We still need to systematically investigate which mitochondrial functions are the most important.

Quintana: We observe spontaneous mitochondrial transfer in the nervous system, particularly at neuron-glia connections, in both healthy tissue and in pathological contexts, such as glioblastoma. The latter represents another dimension of transfer, where cancer-neural connectivity and mitochondrial exchange are emerging as key factors in cancer progression. We see that, in physiological contexts, transfer occurs spontaneously and is regulated by specific molecular players involved in intercellular communication and dynamics. Notably, we observe that different ways of transfer or mitochondrial acquisition serve to reconfigure the mitochondrial signature and metabolism in the nervous system and glioblastomas, with the potential to modulate their physiology and offer new venues for therapeutic interventions.

Recommendation

Having been involved in this topic for some time, MitoWorld has discussed a simple step toward moving from debate to a methodology to review what is being discovered in mitochondrial transfer (endogenous) and what is being performed in mitochondrial transplantation (exogenous). Here are the suggestions and more are welcome from the community.

- Establish a working group to track developments

As Brestoff, Keshav, et al. did with nomenclature, MitoWorld suggests the establishment of an agreed-upon tracking system for transfer and transplantation activity. This could be a formal registry, an inventory, or catalog. It will include common terminology and naming of activity, methods, collection, evidence, results, conclusions, and recommendations. We are asking a number of researchers to help in this process.

- AI review of literature and associated data

MitoWorld has a relationship with Heureka Labs, developed in part by mitochondrial and metabolic researcher and AI specialist Matthew Hirschey, PhD (Duke University School of Medicine). Heureka will develop an initial approach to use AI to index past research for categories of activity and to develop data standards for analyzing and synthesizing data and processes.

- Basic science and the phenomenology of mitochondria

There is still much to learn about our endosymbionts, the mitochondria, along with their DNA, and the complex mitonuclear system. Mitochondria have suffered years of obscurity in many forms of research and medicine. They have been typecast as the powerhouse of the cell. mtDNA is just beginning to be a larger topic, with the first conference on the subject having been held this summer in Nashville, Mechanisms of Mitochondrial DNA Mutation and Repair. We would like to see the still poorly understood mechanisms of mitochondrial biology become more central to funding agencies around the world, as it is increasingly apparent that mitochondria, as the hubs of metabolism, are central to the health of our cells.